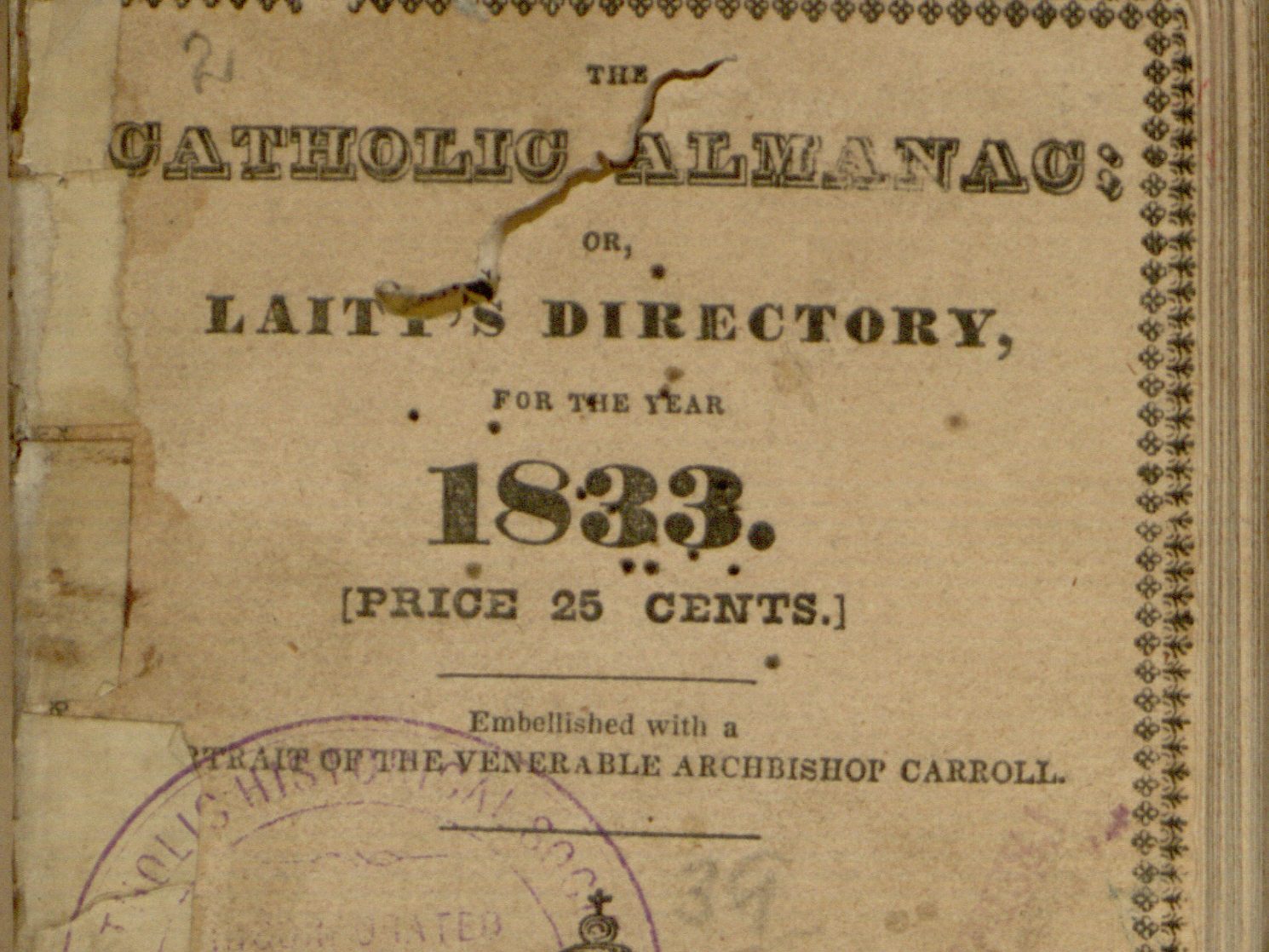

Between 1833 and 1853, Catholicism in the United States experienced remarkable growth, transforming from a minority faith into a significant religious force. This expansion, fueled by waves of Catholic immigrants, particularly from Ireland and Germany,[1] is vividly documented in the Catholic almanacs of the period. The 1833 United States Catholic Almanac, or Laity’s Directory, published by James Myers, and the 1853 Metropolitan Catholic Almanac, published by Fielding Lucas, Jr., provide detailed snapshots of this transformative era. Despite differences in publishers and the inevitable variation in methodology for collecting information, both almanacs were widely regarded as reliable by the public and ecclesiastical authorities, serving as trusted resources for tracking contemporary Church information and statistics.

In 1833, the Catholic Church in the United States was still in its early stages of development, as documented in the United States Catholic Almanac. This almanac details a modest but growing network of dioceses, parishes, and institutions, comprising 264 churches and nine cathedrals. Many parishes, particularly in rural areas, relied on a single priest who served multiple congregations, holding services on designated Sundays. For instance, in Maryland, Rev. Francis Rolof alternated between locations like Bryantown and Zachiah to meet the needs of scattered communities. The almanac also highlights the significance of early Catholic colleges, such as St. Mary’s College in Baltimore and Georgetown College in Washington, D.C., which played a crucial role in educating Catholic youth and clergy. A total of seven colleges are recorded, laying the foundation for Catholic intellectual life.[2]

By 1853, the Metropolitan Catholic Almanac showcased a remarkable expansion of Catholicism. While less detailed than the 1833 edition, likely due to the overwhelming growth in parishes and clergy, the 1853 almanac reports 1,545 churches, representing a 485% increase over the previous two decades. It also notes 34 dioceses, suggesting a 277% rise in cathedrals if each diocese had one constructed. Additionally, the number of colleges surged by 542%, reaching 45 institutions, referred to as “men’s literary institutions.” This growth reflects the Church’s response to massive immigration, particularly from Ireland and Germany, as well as the nation’s westward expansion, which necessitated the establishment of new parishes, dioceses, and educational facilities to serve a rapidly growing Catholic population.[3]

In 1833, the United States Catholic Almanac lists dozens of churches across states, many of which were still under construction or served intermittently, such as the undedicated churches in Maine and Rhode Island. By 1853, the number of parishes had increased significantly, particularly in urban centers such as New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, where Irish immigrants were concentrated. The establishment of new dioceses, such as those in Monterey, CA, and New Mexico, Nebraska, and the “Indian Territory,” further underscores this expansion.

The dramatic expansion documented in these almanacs, from rural mission churches to prominent urban cathedrals, was driven by the arrival of over a million Catholic immigrants, primarily from Ireland and Germany, between 1833 and 1853. These immigrants, fleeing famine and political unrest, established a lasting legacy by building vibrant Catholic communities despite fierce nativist resistance, including the 1834 burning of a Boston convent[4] and the 1844 Philadelphia anti-Catholic riots.[5] By 1853, these immigrant contributions had firmly rooted Catholicism in American society, with a network of parishes, schools, and colleges that endured as a testament to their faith’s cohesive communities and the organizational strength of Church leaders.

[1] For Irish immigration see Margaret Mulrooney, Fleeing the Famine : North America and Irish Refugees, 1845-1851 (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2003), xi, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/liberty/detail.action?docID=492149, and Ciarán Ó Murchadha, The Great Famine : Ireland’s Agony 1845-1852 (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2013), 160-61. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/liberty/detail.action?docID=5309713, for German immigration see Farley Grubb, German Immigration and Servitude in America, 1709-1920 (Oxford, UNITED KINGDOM: Taylor & Francis Group, 2011), 410-11, 13. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/liberty/detail.action?docID=1099479.

[2] The United States Catholic Almanac, or, Laity’s Directory, for the Year 1833 (Baltimore: Published by James Myers, 1833), 40-84, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CY0112457516/SABN?u=vic_liberty&sid=bookmark-SABN&xid=4ed03405&pg=40, Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500-1926.

[3] The Metropolitan Catholic Almanac and Laity’s Directory for the Year of Our Lord (Baltimore: Published by Fielding Lucas, Jr., 1853), 246, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CY0111827051/SABN?u=vic_liberty&sid=bookmark-SABN&xid=6846b77c&pg=246, Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500-1926.

[4] Nancy Schultz, Fire and Roses: The Burning of the Charlestown Convent, 1834 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2002), 3-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=TlGW-kfYCpQC.

[5] Steven L. Danver, Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2010), 325-27. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/liberty/detail.action?docID=664542.